With many Europeans coming back from holidays, their minds full of travel memories, we suggest staying in this ambiance, and to learn this month about how products now travel between Europe and China. Since the President XI Jinping unveiled the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative in 2013, most commentators agree to qualify this gigantic project as a political project first and foremost. Nevertheless, it has mainly concretized in infrastructures’ investments so far, and one of the most visible impacts is the organization of a new – or improved – logistics network. What are the concrete benefits that European companies can get from the OBOR initiative? What is existing today, and what is still to come? To answers these much commented on questions, VVR went to see M. Joost van Opstal who works at AEL- Berkman, a logistics company. He answered our questions below:

To start with, let’s explore what is OBOR today. How can one know about all the new infrastructures built within this initiative? Which organization does a follow-up on this huge project?

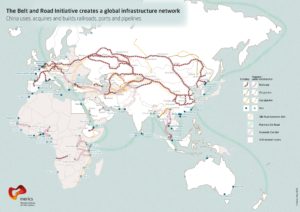

Right now, OBOR is made of two land corridors: China-Mongolia-Russia and the Southern road, also called the Khorgos way (China – Kazakhstan – Russia – Europe). These roads are aimed at connecting inland China to Europe in a more efficient way. Indeed, for factories that moved to Western China, because of rising labor costs on the coast, the transportation from these inland cities to the Chinese harbors sometimes took up as much cost as the whole transportation from these harbors to European harbors! The two largest hubs on the Chinese side are Chongqing and Zhengzhou. In Europe, the entrance terminal is in Poland, where the custom clearance is done – this rail freight is organized on the same principle as maritime freight: one unique customs document is used for the whole transportation process. Most of the goods for Western Europe then go through Duisburg in Germany.

It is to be noticed that most of the rail network used today under the OBOR name actually existed before the launch of the initiative, which explains that it has been operational so fast.

To know about the advancement of the projects (in pink on the above map), there are constant seminars by consulates and embassies, mostly focusing on the impact on the local country’s economies. All in all, official governmental channels are reliable information sources, as well as the companies involved and the ones who sell this project – such as the Khorgos Gateway. There, one is sure to get the most recent information, but they might be lacking some critical insight.

Which impact do you see OBOR has on European businesses?

The impact is mainly on logistics. As a matter of fact, HP is one of the companies at the origin of the initiative, together with the Chinese government and got involved for that reason. Having moved their entire production to Chongqing, they needed an alternative transportation road for their short-life products. In this technology field, two weeks can be the difference between selling and not selling.

Thus, rail freight comes as an alternative for our clients. However, it is merely an alternative, not a replacement: it will not get over 10% of the transportation on the Europe-China freight lines. Compared to maritime freight, rail freight through Central Asia is faster and not subject to so many time and cost variation, while being approximately three times the cost of maritime freight. Until now, the Maritime Silk Road did not lead to much change in the way the maritime freight is operated from China to Europe. Compared to air freight that is mostly used for perishable goods such as food, rail freight is less expensive, allows for bigger quantities and imposes less restrictions when it comes to dangerous goods. Besides, this new rail network now allows for a reasonable travel time and suitable transportation conditions for these perishable goods.

Another much discussed benefit is the larger playing field OBOR would create for European businesses. Indeed, Chinese authorities also claim a development aspect in this project, which would theoretically lead to the creation of a market of 4.4 billion of customers when one counts all the 68 countries involved today. This information yet need to be nuanced as a large majority of these people have today small income. This gigantic market is thus highly conditional on the success of the development part of the initiative.

What risks do you see linked to the use of the OBOR rail network?

Concerns voiced by our clients revolve mainly around two points: the quality of the transportation infrastructure and the security.

When a problem occur on the train, how is it fixed? This concern is especially high for refrigerated products. Although OBOR officials claim that there is a maintenance station every 8 hours, experience says otherwise.

Another particularly acute concern is the risk of theft, mainly for technological products with a high added-value, as the convoy cross poor areas. Incidentally, one can assess the development of Chinese private security companies’ services along the road, showing that this concern is justified. However, reality shows that this happened so far mainly in Europe.

Of course, a political risk remains as some railroads cross many countries, that are either domestically unstable or with unstable relations with one another.

What type of industries have the most to gain from OBOR?

These industries are without doubt retailers in electronics (laptops, computers), fashion, short-life products (milk powder, agricultural products), machine (spare parts), and pharmaceuticals.

Besides, most of the traffic happens from China to Europe (90%), from suppliers to distributors. For instance, companies who supply distributors such as Lidl must deliver their products fast: a one-day difference can lead to a penalty. Before air freight, which is extremely expensive, was the only option. Today the train offers a cheaper alternative.

The traffic from Europe to China is only 10% of the total. Yet, given the flow size, these 10% can still be very interesting. A very interesting business case is the one of a Dutch powdered milk company. Using OBOR roads enabled them to develop very successfully in China when they have now a Joint-Venture. Today, they use weekly trains connecting the Netherlands to China. All in all, the products that can benefit the most in this direction are: milk powder – today a large part of the exports; agricultural products – mainly fresh vegetables; and pharmaceuticals.

Another benefit we identify for European companies lies in marketing. Indeed, using this way of transportation is environmentally friendly, and socially responsible. Besides, because of the political value attached to this initiative, it might be possible to receive subsidizes too.

The development of cross-border e-commerce is often mentioned in reports. However, the logistics are then different from retail and do not include rail transportation as the volumes are too small.

What are your thoughts on the way OBOR is going to evolve? What is in it for the future?

The scope of the project became so wide, and so many factors are at play that it is hard to predict how it will evolve, if it will reach the official goals or not. From the information we can get in China, there is no sign of new railway being constructed between Europe and China.

Besides, we see that it already reached some limits today, in terms of volume. With 2 trains a week from every end-city the project encompasses, European hubs are encountering congestions issues.

Established in 1903 in The Netherlands as an energy and coal provider, Berkman Energy service became the starting platform for what has grown from a family business into a global entity. Established in 1998, AEL-Berkman Forwarding (HK) Ltd. started off as a joint venture between two highly experienced and professional freight forwarding organizations. With a combined experience of more than 50 years in this business, AEL Asia Express (HK) Ltd. and Berkman Forwarding B.V ventured together with the objective of developing the China market. They organized their first rail freight on OBOR roads in 2016.

By Manon Bellon